To read full article, follow this link:

https://www.vogue.com/slideshow/walt-cassidy-waltpaper-newyorkclubkids

vogue

To read full article, follow this link:

https://www.vogue.com/slideshow/walt-cassidy-waltpaper-newyorkclubkids

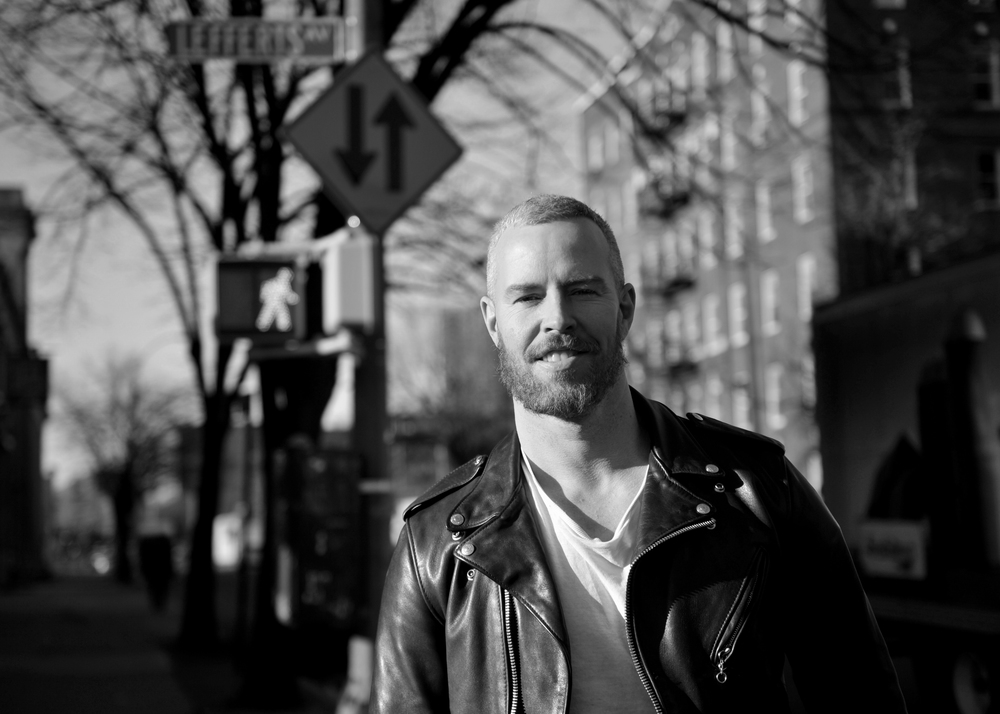

Walt Cassidy in his studio in Prospect Park

Wearing worn-out blue jeans and a white t-shirt, Walt Cassidy greets me at the door of his Prospect Park studio for our photo shoot. A hallway leads us to a living room filled with photographs by Kenneth Anger. His own artworks, including a large brass sculpture, hang across the room to the right. To the left stands a small meditation altar. The room is filled with the earthy scent of sage, the herb Cassidy uses to cleanse his apartment before daily meditations.

Standing at 6’3” and 220 lbs., Cassidy’s physique is impressive - arms covered with tattoos, bicep muscles bulging under his tee. With a closer look, his tattoos reveal to be not just ink on the skin, but rather like words in a diary - story-telling imagery intrinsically weaving together life and art in an expression of “chrysalis”, of evolution and transcendence. But unlike his toughness of flesh, Cassidy possesses a gentle disposition, and jokes that he feels like the "Rocky Balboa of the art world". He is streetwise and seasoned, as evident by his biography, but is thoughtful and soft-spoken as we engage in conversation about his latest projects.

Cassidy’s transformation as person and artist is extraordinary, as a simple Google search will show. During the ‘90s, he reigned as Waltpaper in New York City’s underground scene, an androgynous Club Kid who became known for complex style creations and over-the-top antics. Cassidy refers to the ‘90s as an exploratory period in his life, a time when self-expression was encouraged and creativity made it all possible. Although Cassidy is proud of that time in his life, he doesn’t dwell in the heyday of the Club Kids. Much like his art, he’s in constant evolution, transforming experiences into sought-after objects that communicate universal themes of violence, love, and healing.

In this Portrait Q+A, the artist talks about his Missouri upbringing, his life as Club Kid Waltpaper, and his recent collaboration with Derek Lam.

LJ: You have several tattoos on your body, the giant spider spanning across your ribs is quite impressive. Is the artwork inked on your body a diary entry like many of your art pieces?

WC: Yes, very much so. I come from a long line of sailors in my family, all of whom were tattooed. My tattoos, like my artwork, I see as utilitarian. Each one represents a particular stage in my evolution.

My father used to fly spy planes for the US Navy, and had his social security number tattooed on each one of his limbs. If ever he were to be blown up, they would be able to identify him. He also had one of his lovers names with a decorative pattern, but the name had been cut out. A slice was taken out and the flesh had been stitched back together creating a scar line. I suppose that was early tattoo removal, you had to cut it out if you wanted it off you. All very functional, “lived in” tattoos.

I like seeing the residue of life’s fumbles, which is what tattooing represents to me. I never approached it from a design perspective, or as an art form. I just did it intuitively, because things happened that I didn’t want to forget.

LJ: When looking at you now, at the tattoos on your body, and the incredible photos of you as gender-bending Club Kid Waltpaper, it’s incredible to see the transformation you’ve undergone over the years. You have spoken of chrysalis as recurring theme in your art work. Tell me about this process of creation and transformation that is so present in your artwork.

WC: I was raised agnostic, with a strong focus on Darwin and the principles of evolution. I lived alone on a farm with my father in Missouri. It was there that I learned about transformation and the cycles of life through raising livestock, riding in rodeos, and growing crops.

For example, I used to be so moved, as a kid, when they would light the fields on fire, known as controlled burning. The purpose was to clear away all the tangles of brush and create grazing fields for the livestock. After the flash of the blaze, the firetrucks would come and hose down the fields with water. In the morning, the wet blackened landscape looked like it was made of velvet. About a week or so later, these tiny slivers of the brightest green grass would emerge, penetrating the dark silhouette of the previous landscape with new life.

This ritual, along with others, reinforced in my psyche the necessity for rejuvenation. Change and evolution are things I have always moved to initiate, cultivate and harvest in my life and my work.

My artwork is inherently paradoxical and allegorical, two concepts that point to this notion of chrysalis. Metaphoric obstacles and their subsequent means of escape are consciously built into the work, allowing a sense of evolution to breathe within the ongoing narrative that I am seeking to illustrate. This breath sustains the current of hope that runs through the work. So there is often a balancing act playing out between dark and light, or chaos and order.

There is an undercurrent of violence in my work, but I utilize the decorative aspects to code much of it. Transformation and illumination, or any form of growth, is always somewhat informed by the notion of violence. But I tend to whisper my violence. It’s never horrific, demanding, or loud.

LJ: From the androgynous Waltpaper of the 90s to the muscular man you are now, was that transitional time in your life difficult to navigate?

WC: There was a lot of trial and error, and it took about ten years for the dust to settle. I established myself as Waltpaper from 19 - 25 years old. I was embraced by the nightlife scene that was thriving in New York City during the 90’s, and I felt very protected and inspired by that system. When it was attacked by the city government and destroyed, I was left a bit traumatized, confused, and completely unsheltered.

Physically my body and face began to change after 25. The androgynous creature that had emerged effortlessly before, started to become a mask. I was becoming a caricature of myself, which didn’t sit well with me. I had studied the Warhol Superstars quite a bit, because The Club Kids were always being compared to them. I saw that many of them, if they survived, where quite bitter, and seemed to remain stuck in the past, the 5-10 year window of their young adult lives. They appeared to be addicted to their own stories of who they were. I didn’t want to follow in that path.

I developed an interest in athleticism and the gym while I was involved with the hardcore band BOOB, in order to remain fit for performing. I was also recovering from many years of heavy drug use. I grew out my beard for the first time, and most people were appalled. It was before the explosion of the bear scene and “the hipster” hadn’t yet been cloned as an identity. Beards were not at all a part of the vernacular in the late 90’s. So it’s interesting to see it so widely embraced as an aesthetic today.

I became more sexually explorative at this time, too. Having come into puberty during the early days of the AIDS crisis, it took me a while to really feel comfortable exploring sex, outside of having the occasional boyfriend. By the late 90’s, there was a lot more awareness about transmission, and new treatments for HIV were developing. So that combined with my age, and changing physicality, offered me some comfort in moving around sexually.

These were all proponents in my identity progression, and each dimension offered up it’s own set of challenges that needed to be overcome in order for me to fully mature as a man.

LJ: The 90s was a thriving, vibrant period in history for queer art and culture in NYC. How do you see queer culture in NYC now? Has it lost the spontaneous, subversive energy of the 90s?

WC: I stay away from negating the present moment and over romanticizing the past. People get so addicted to nostalgia. I try to practice some restraint with all of that, as it becomes a very slippery slope. At the same time, I adore history and have a great respect for it.

Today’s New York feels much more mainstream, and is about being commercial and accessible, therefore we have become more compartmentalized, self referential, sterile and streamlined. We are a profile culture. It’s all about packaging and selling. There is not much ambiguity, very few blurry lines, and there is a lot of appropriation. Perhaps this is due to the accessibility of information and references through the internet. At times, I feel things can get ‘over-sharpened’, metaphorically speaking, and they require some softening.

Artists and creatives will always respond to whatever cards are on the table and try to utilize them within the production of their work. There will always be leaders and followers in every decade. This is true now, as it was in the 90’s.

The term queer feels really dated to me, especially as the spectrum has become more refined in reflecting the varying dimensions of gender identity and sexuality. I realize that ‘queer’ is a blanket term, but beyond it’s casual use, it seems that the identity of queer is a subscription to a retrogressive system that cannot really be accurately applied to the contemporary dynamic, without over simplifying to the point of offense.

The notion of ‘queerness’ seems to be dependent on a structure within society of mainstream vs. alternative, and that doesn’t really exist anymore. Transparency and accessibility of information surrounding cultural gesture seems to render this traditional binary structure as mute. It’s really a whole new game, and the 90’s feel just as distant as Ancient Rome to me.

LJ: Your jewelry work has been profiled at Vogue Magazine and you have recently designed pieces for Derek Lam's SS16 collection. What does it mean for you to have validation from the fashion world? Was this something you aspired or did it come as as surprise?

WC: I did not have any fashion agenda in making the jewelry. It started as an art project and as a way for me to test materials that could potentially be translated into sculptural form. I've also enjoyed using the jewelry pieces in my portrait photography and love the connection to the flesh. It adds another layer within the portraits. Cross pollinating media is commonplace in my work.

Additionally, I wanted to make the jewelry for my collectors and friends. I realized many people in my circles couldn't accommodate a sculpture, drawing or photo, but would be able to access my work through smaller more affordable jewelry pieces. So, I continued to walk down that path.

And then Vogue called. They loved and understood everything that I was doing, and were in full support. They appreciated the authenticity of the work, which was incredibly refreshing for me. I haven't had much mentorship on my creative journey. For the most part, I have been a tribe of one. I am not a part of any scene or clique of people, so it was invigorating to have someone as powerful as Vogue come along and give me their stamp of approval. I have developed some wonderful friendships at Vogue and they continue to support and guide me on this road into fashion that I had not planned on going down. It's exciting.

My collaboration with Derek Lam evolved from my connection to Vogue, and I found his energy and understanding of where I am coming from as an artist to be in line with my experience at Vogue. He was willing to let me do my thing, but also gently guided me into some new territory. His team is so balanced, the energy is so good at his studio, and everything just flowed naturally. As a collaboration, we achieved a nice combination of contrast and compliment.

LJ: What's next for you?

WC: This whole experience has forced me to raise the ceiling for myself and to think outside of the very tight "artworld" box. I have completely restructured and re-conceptualized my studio as an autonomous business. Everything operates in direct relationship to the studio, including all sales. I am finding in today's world, collectors want direct contact with the artist. It's a very intimate relationship between artist and collector. Our energy is intertwined via the shared connection through objects, and I greatly respect the purity and tenderness of that connection. I have learned to be more mindful of how this energy exchange is facilitated, and maintain a bit more control than I have in the past.

In terms of what's next, I have been approached by a couple international brands about doing collaborations, so we will see how those play out. My primary interest is in expanding my materials and production and building teams around my ideas. Having worked on my own, almost as an outsider artist, for so long, I am keenly interested in collaborating with larger companies and utilizing their resources to translate and launch my ideas. I see my work manifesting in a wide range of materials such as glass, stone, leather and precious metals. I am extremely interested in furniture and dealing with spaces that are lived in. So that could take me down many roads.

I have so much that I want to do. It's turning into a very broad journey. For many years I have felt a bit like a caged animal. Now is perhaps the moment when the animal turns on his captor. The hunter gets captured by the game.